By Christina Murzynski, Clinical Mental Health Intern

It has been said that loss plays an intrinsic role in the human experience. If all things eventually must end, then grief might be considered a natural response to those endings. But what constitutes a “natural” response to loss? If what it means to feel grief–shock, disbelief, sadness, guilt–or what it looks like to experience grief–loss of motivation, of appetite, of the ability to think straight–seems a bit varied and nebulous, that’s because it is!

Grief in the Modern Age

Because there are so many ways to experience a loss it can also be difficult to fold all experiences of grief into one, neat definition. This shows up in how hard it is to communicate grief. How many of us have struggled to know how to convey understanding and comfort to a bereaved friend after the death of a beloved pet or grandparent, only to settle on “I’m sorry for your loss”, a hug, or a Hallmark card?

Social scripts in the United States surrounding grief are not patterned to any easy or “natural” alleviation of this invisible pain, but to the needs of the workforce and keeping up appearances. According to the Society of Human Resource Management, despite the psychological research indicating 20 days as the most appropriate amount of leave before returning to work, 4 days is the average bereavement leave policy for employees who have lost a spouse or a child, reduced to 3 days for the loss of a parent, grandparent, domestic partner, sibling, grandchild, or foster child (Roepe, 2017).

Modern American death rituals too, don’t seem to be adapted for mourners, but for everyone around them. Across almost all faiths, economic levels, and cultures, the balance between doing your social due diligence and receiving social support can be a tenuous one. Even in the most psychologically advantageous of rituals, there comes a point where the body must be stored at its final resting place; when the casseroles stop coming and your neighbors return to their own concerns. You may stop being asked about the loss at all and be expected to return to your normal routine. Life rolls on.

So then you get over it, right? If only things were so simple!

Note that above, we are using the death of a loved one as an example, as this is the primary loss with an associated ritual acknowledged openly and publicly by our society. Even if we wanted to, we do not perform funerals for break-ups, hold wakes for deceased pets, or write obituaries for lost jobs.

However, for those experiencing these losses, or other types of disenfranchised or anticipatory grief, it isn’t as though there’s nowhere to turn for social reinforcements during a dark time.

Grief and Social Media

As of 2023, a record 4.9 billion people worldwide use at least one form of social media–the average person having six to seven accounts. Some part, small or large, of our lives has moved to (and continues to grow) online. We are represented somewhere beyond what is immediate and tangible, and yet, viewable for people we know and people we don’t.

As of 2023, a record 4.9 billion people worldwide use at least one form of social media–the average person having six to seven accounts. Some part, small or large, of our lives has moved to (and continues to grow) online. We are represented somewhere beyond what is immediate and tangible, and yet, viewable for people we know and people we don’t.

But social media presents something of a double-edged sword to those seeking connection online; 73% report finding support and comfort during difficult times, while 67% of adolescents struggle with self-esteem due to what they are seeing online (Wong, 2023).

If our accounts are truly a reflection of our lives, for better or for worse, one might assume they become a reflection of our mourning, or public grieving process, as well.

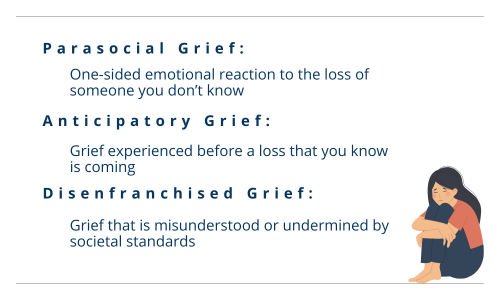

Parasocial grief, a one-sided emotional reaction to the loss of someone we don’t know, is often what best describes what goes on under the #RIP hashtag when a beloved celebrity passes on.

Anticipatory grief, or the grief experienced before a loss that you know is coming, can be an emotional reckoning all on its own–common amongst individuals caring for loved ones at the end of life, including (based on hundreds of thousands of Tiktoks and blog posts on the subject, ranging from humorous to grave) our beloved pets.

Disenfranchised grief is a term utilized for situations where one’s grief is undermined and misunderstood by societal standards–those who have lost a friend that they met online, for instance, often find that their sadness is misunderstood by peers who don’t understand such a reaction on behalf of “someone you’ve never even met”.

All of these sentiments find a home on social media, maybe more so than any other social context we find ourselves in. Research points to the idea of sharing being “disinhibited” on social media, where any obvious discomfort in sharing such intimate thoughts of mourning where coworkers, acquaintances, friends, or family might see them is softened by the barrier of a screen (Walter, 2015). I cannot have the local newspaper post an obituary for my deceased dog, but I can dedicate an Instagram post to her, where my friends and family can console me in a time of need and remember her fondly. Maybe I can only vent to my friends for so long about a failed relationship with someone who I truly thought was “the one”, but what is stopping me from commiserating with those in a similar situation on anonymized chatrooms, forums, or Reddit threads?

What does it imply to post about our losses on social media? Is social media more of a public park, a town square, or a private residence? Is it a performance, any more so than funerals and wakes? Some might call this “grief posting”, a threat to a call for privacy. Others might see it as radical vulnerability.

Grief and the Dual Process Model

If you are a client of mine, the likelihood that you recognize the image below is very high.

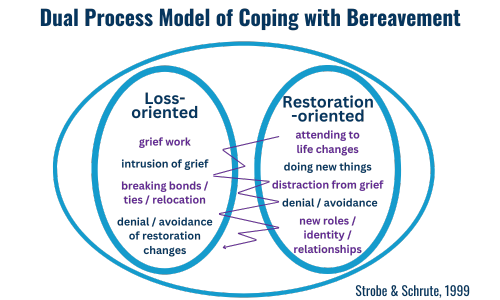

In 1999, researchers Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut published their Dual Process Model framework as a direct response to the idea of “grief work”, a then-popular idea that a griever must undertake the hard work of tasks and stages, all the while confronting their difficult emotions, should they ever hope to recover from their loss. Stroebe and Schut considered this idea of “grief work” to be vague, inconsiderate of the fluid, dynamic process of coping, and exhausting to an already exhausted griever. Grief work sets expectations for recovery awfully high–proceed neatly through a series of delineated stages, no distractions, no back-sliding, or else what? Suffer under the weight of your grief forever?

The Dual Process Model (1999) offers an alternative to this line of thinking. Rather than move stage by stage, grievers oscillate back and forth between two types of stressors, and thus, coping methods.

The first type of stressor are the loss-oriented stressors, or the actions and feelings that arise from the loss of the person, job, pet, or relationship itself. These stressors may be sustained, focused, and intentional (looking at old photos, recalling memories, imagining what would be different if the loss had not happened) or sudden and intrusive (such as being out at the store and seeing something that triggers thoughts of the loss). This is almost exclusively where our idea of grief work and all its confrontational ‘processing’ lives; yet, it’s only the first half of this model. So what’s left? What might need to happen to the empty space left behind by a loss? What is the opposite of loss?

Stroebe and Schut answer that simply: restoration. Secondary sources of stress and coping, thus, is where the consequences of the loss live: feelings of isolation, needing to adapt or fulfill new tasks due to the loss, and the rebuilding of one’s everyday life. The Dual Process Model, as the title suggests, encourages treating these actions as just as important as any head-on processing that must be done as part of the grief work.

Sitting in your feelings, crying, and reminiscing on the loss-these are all important, painful, cathartic forms of healing! Taking a dual process approach to healing suggests, however, that doing your laundry can also be a form of healing. The practical tasks that must be taken up in the wake of a loss? Healing and coping. Distractions? Also coping! Taking breaks and getting rest? That counts! The idea is to not dwell too intently in one area of coping over another–such as distracting yourself so much that you never process the loss, or working so intently at grief work that you ignore the other people, places, or roles in your life.

So what does social media have to do with this oscillating? Within reason, everything!

#Grief #DualProcessModel #WhatComesNext

The reasons millennials give for posting about their grief are not so different from our reasons for engaging with anything at all: it’s become normalized, it announces the loss to those who might not have otherwise find out, it provides a space to process feelings and generate support (King, 2022). But there can also be complicated feelings about doing so: Am I making this loss about me by posting about it for support? Is it asking too much of others to care? Are the condolences and commemorations enough, or are they a distraction? At the end of the day, the griever wants to know, “is this working? Will posting about my grief online make me feel better?”

Does sharing grief online via social media work? As the Dual Process Model would suggest, not on its own. To that end, no singular tactic for grieving and healing “works” on its own. It’s the back and forth between many tasks, a lot of complicated feelings, and passage of time that eventually heals us. Nebulous and vague? Sure, but so is grief itself.

Grief can be a long journey only made longer by attempts to go at it alone. All things end–accepting this and bidding others to take up the task of grieving with us in community, can seem daunting and often is in our hyper-individualized culture. At least, until the call to action shows up in the form of an Instagram photo, a tweet, or a blog post.

For more information about death rituals on a societal level, I recommend checking out The Order of the Good Death.

Sources

King, R., & Carter, P. (2022). Exploring young millennials’ motivations for grieving death through social media. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 7(4), 567–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-022-00275-1

Roepe, L. R. (2017, August 17). How to support employees through grief and loss. SHRM.https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0917/pages/how-to-support-employees-through-grief-and-loss

Stroebe, M. & Schut, H. (1999). The Dual Process Model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23(3), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046

Walter, T. (2014). New Mourners, Old mourners: Online memorial culture as a chapter in the history of mourning. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia, 21(1–2), 10–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614568.2014.983555

Wong, B. (2023, May 18). Top social media statistics and trends of 2023. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/business/social-media-statistics/